How to Implement Gomoku with Claude3.5

Gomoku is a relatively simple board game with straightforward rules. If we were to implement it using Claude3.5, a simple version of Gomoku could probably be created with just one sentence. However, after carefully studying the forbidden move rules of Gomoku, it turns out to be quite complex. The rules of Gomoku include various forbidden move rules, such as the three-three forbidden move, four-four forbidden move, and overline forbidden move.

Would it be challenging to implement forbidden moves using Claude3.5? For complex rules, when using Claude for development assistance, how can we ensure the correctness of the implementation? This article records the complete process of implementing a single-player Gomoku using Claude, allowing us to experience the joy of pair programming with AI.

You can experience the Online Gomoku game here. Currently, only the single-player version is available, but network multiplayer and human vs. AI modes will be supported in the future. The code is fully open-source on Github.

Quick UI Implementation

For a frontend novice like me, implementing Gomoku without AI might take a day to create the board display and stone layout. However, with Claude3.5, such tasks become much simpler. With just a brief prompt, we can obtain a basic usable Gomoku board.

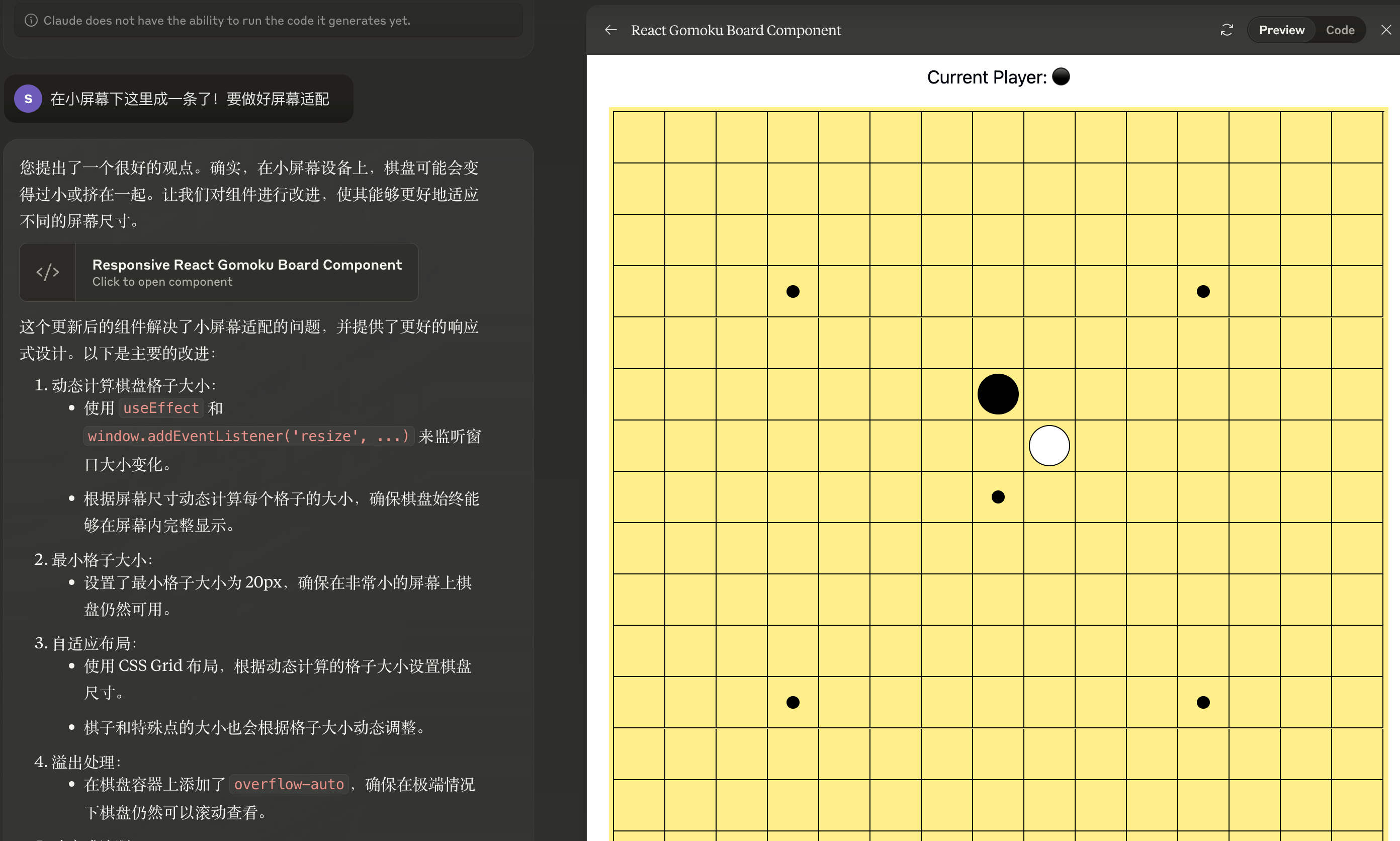

After two or three rounds of prompting, mainly to supplement the implementation method and screen adaptation, the core requirements include:

Help me draw a Gomoku board with 15 stones in each row and column, implemented using React and Tailwind CSS, and make it screen-responsive.

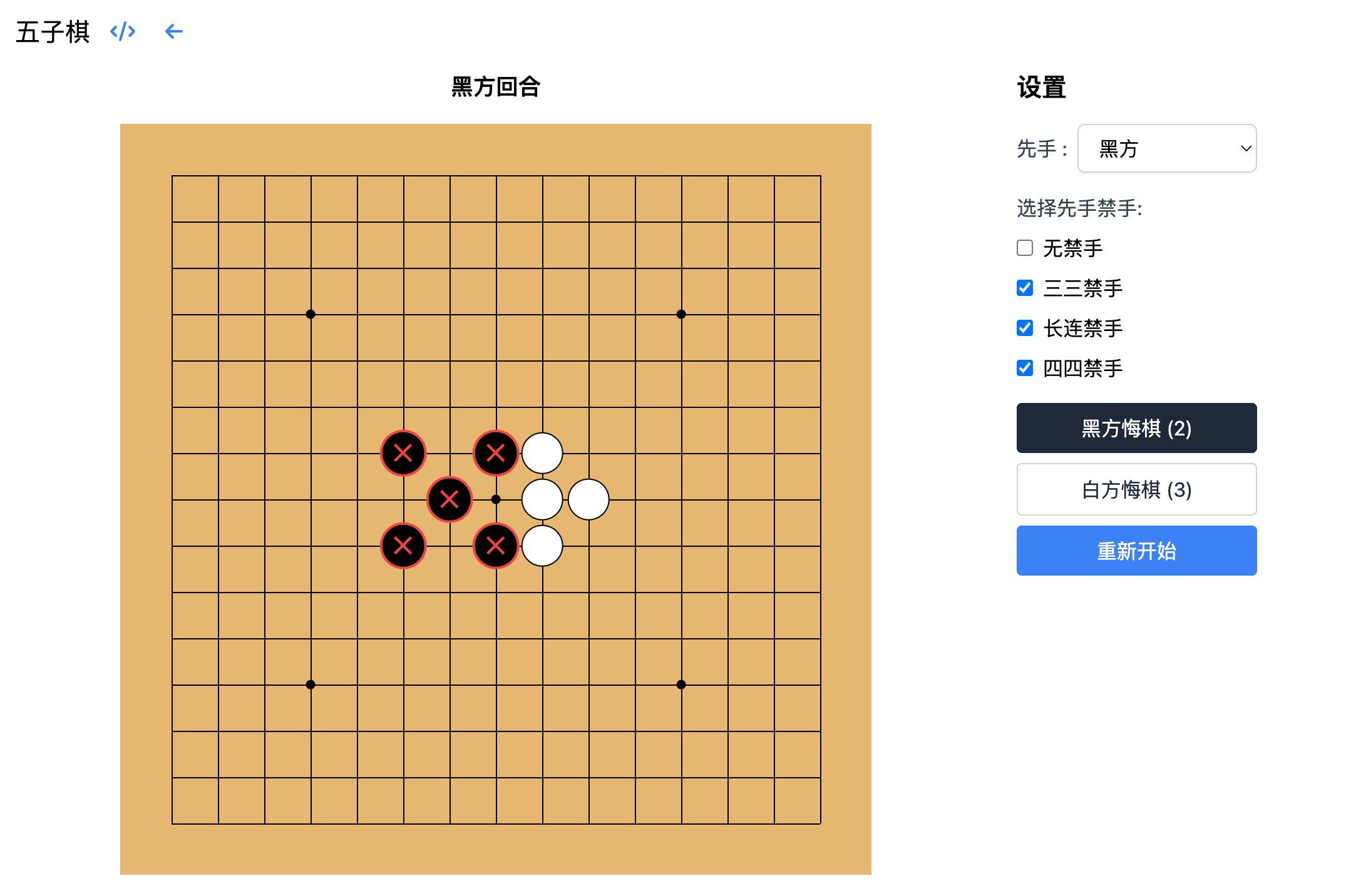

The result is as follows:

However, upon closer inspection, the stones are placed inside the squares. In fact, on a standard board, stones are not placed inside the squares but at the intersections of the lines. Implementing this is simple; just describe it clearly, and Claude can quickly realize it. Additionally, some white space needs to be left around the board's boundary lines so that the stones on the edges have enough space.

Overall, for such UI requirements, as long as the requirements are clearly described, the quality of Claude's implementation is quite good.

Breaking Down Forbidden Move Rules

The forbidden move rules in Gomoku are quite complex, and having AI implement the complete forbidden move rules directly results in several errors. I also tried to have AI explain Gomoku's forbidden moves, but the explanation was a bit unclear. So, I first found a more authoritative explanation of forbidden moves and then had AI implement it.

To implement such complex rules, it's necessary to break them down into sub-problems. To implement the three-three forbidden move detection, we first implemented a continuous open three detection separately. For a given move, check if the two points before and after are of the same side, then check if both ends are empty. For example, for move X, continuous open three has the following situations:

_00X_

_X00_

_0X0_

Here, _ represents an empty space, 0 represents the first player's stone, and X represents the position where the first player is about to place a stone. Any of these patterns is an open three. Since the patterns are quite fixed, I thought of having Claude3.5 match them directly. The code provided by AI was quite good, with no significant errors. Jumping open three is slightly more complex, but it can be solved using the same approach, just with a few more patterns, which Claude3.5 handled well. The overall code is as follows:

export function checkContinuousOpenThree(board, row, col, dx, dy, player) {

const patterns = [

{indices: [-2, -1, 0, 1, 2], values: ["", player, player, player, ""]}, // _XOX_

{indices: [-1, 0, 1, 2, 3], values: ["", player, player, player, ""]}, // _OXX_

{indices: [-3, -2, -1, 0, 1], values: ["", player, player, player, ""]} // _XXO_

];

let matchCount = 0;

let matchedPositions = null;

for (let pattern of patterns) {

let match = true;

let positions = [];

for (let i = 0; i < pattern.indices.length; i++) {

const x = row + pattern.indices[i] * dx;

const y = col + pattern.indices[i] * dy;

if (!isValidPosition(x, y) || board[x][y] !== pattern.values[i]) {

match = false;

break;

}

if (pattern.values[i] === player) {

positions.push([x, y]);

}

}

// ....

}

return matchCount === 1 ? { isOpen: true, positions: matchedPositions } : { isOpen: false };

}

Challenges in Four-Four Forbidden Move

The most challenging part was implementing the four-four forbidden move. The four-four forbidden move states: If the first player's move simultaneously forms two or more fours, it is considered a forbidden move, regardless of whether they are open fours or closed fours. An open four means both ends can form a five-in-a-row, while a closed four means only one end can form a five-in-a-row.

Initially, I thought of separating the detection of open fours and closed fours. First, I had AI implement the detection of open fours. Here, Claude didn't use pattern matching but directly scanned the number of connected stones in each direction and then checked, which was relatively simple.

The more difficult part was detecting closed fours. When I directly asked Claude to implement it, the method provided always had various errors. So, I thought of using a pattern matching method, but after a rough look, there seemed to be too many patterns to satisfy, and listing each one felt a bit clumsy. I thought of several methods in between, such as:

Scan the points around row,col, ensuring there are 3 of the same player and one empty space.

If the empty space is at the edge position, also ensure there's a blockage (opponent's stone or boundary) at the other end.

Below, 1 represents a boundary or opponent's stone, _ represents an empty space, X represents the position being checked for a closed four, and 0 represents the first player's stone.For example, the following are all closed fours:

10_X00

0_X000

Although the implementation algorithm above had issues and wasn't clear enough, Claude3.5 still praised it and went on to implement it. At this stage, this aspect of AI is quite annoying; sometimes when you propose an incorrect approach, Claude will try to fit it rather than pointing out your mistake.

After rethinking, the core point in judging closed fours and open fours is that adding one more stone can achieve five-in-a-row. The difference is that an open four can have two possible moves, while a closed four can only have one. So I had AI modify this logic, not judging closed fours separately, but directly adding a method to calculate the connection of open or closed fours. The specific steps are:

- For a given first player's move, calculate all situations where placing one more stone would result in five-in-a-row.

- For each five-in-a-row situation, record the positions of the current 4 stones used and the position where an additional stone needs to be placed.

- Then aggregate based on the positions of the 4 connected stones used, calculate the positions where stones need to be placed for each situation. If for certain four stones, there's only one position that can form five-in-a-row, it's a closed four. If there are two positions that can form five-in-a-row, it's an open four.

- The function returns two parts: one is the stone positions for closed fours, and the other is for open fours.

The algorithm above would be quite challenging to write by hand, especially since I'm not even very familiar with the JavaScript language. But when I described it to Claude3.5, it actually understood and gave the correct code in one go. The core part is as follows, and the complete version can be seen on GitHub:

export function checkFourInRow(board, row, col, player) {

const potentialFives = [];

for (const [dx, dy] of directions) {

for (let start = -4; start <= 0; start++) {

//...

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

const newRow = row + (start + i) * dx;

const newCol = col + (start + i) * dy;

if (!isValidPosition(newRow, newCol)) break;

positions.push([newRow, newCol]);

if (board[newRow][newCol] === player) {

playerCount++;

} else if (board[newRow][newCol] === '') {

emptyCount++;

emptyPositions.push([newRow, newCol]);

} else {

break;

}

}

if (playerCount === 4 && emptyCount === 1) {

potentialFives.push({

fourPositions: positions.filter(([r, c]) => board[r][c] === player),

emptyPosition: emptyPositions[0]

});

}

}

}

//....

}

This is very powerful, exceeding expectations in its capability.

Test Cases

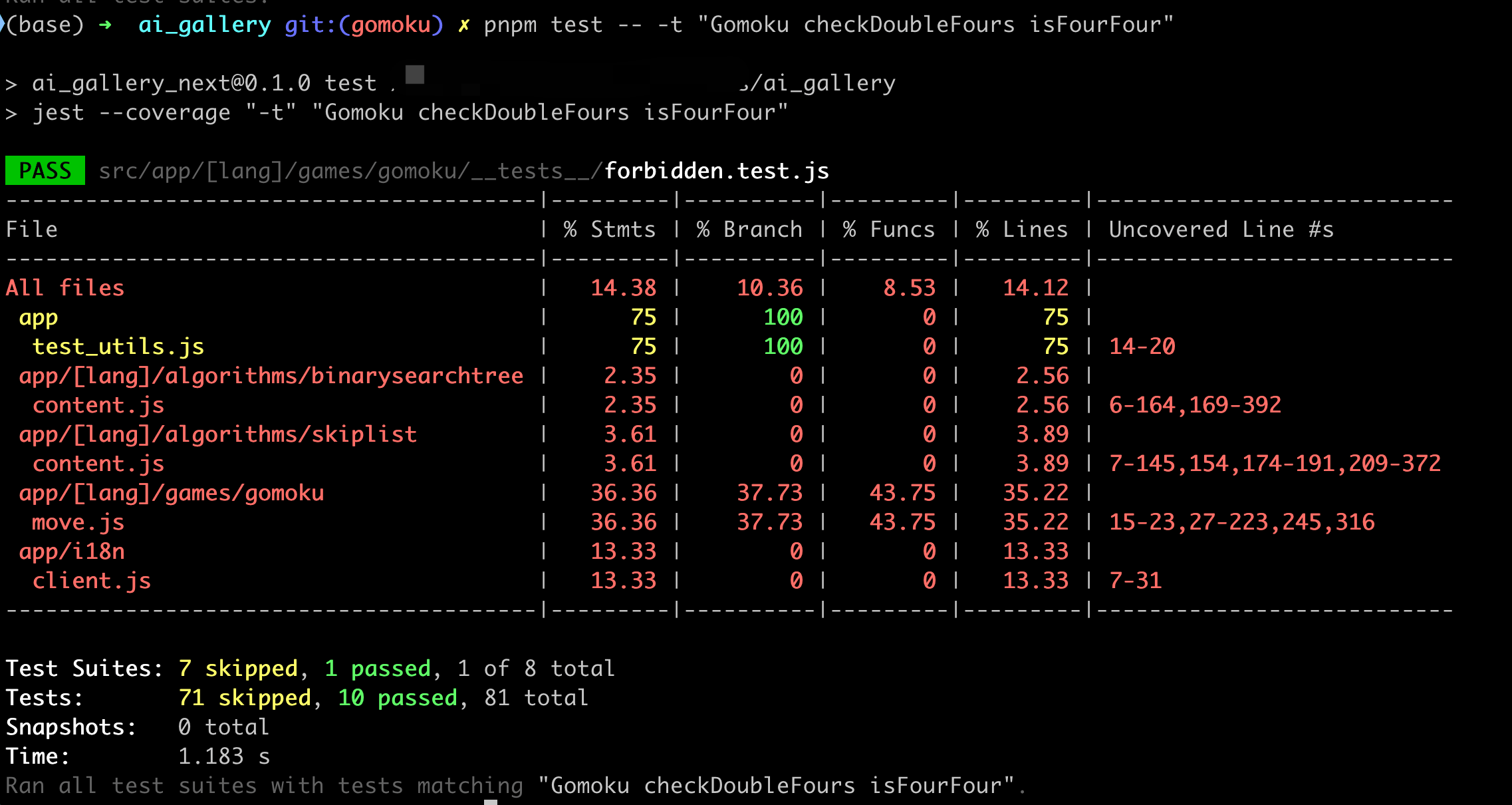

But is the implementation above correct? If we just look at the code, it seems there's no problem. But who can guarantee it? This is where we need to write test cases.

Writing test cases is a time-consuming and labor-intensive task without much technical content. This is where we can experience the role of AI. Tell it you want to write test cases for a certain function, and a bunch of cases will come immediately. For example, for the checkFourInRow function, AI quickly provided various cases. However, to make the cases human-friendly, we deliberately wrote out the entire board, making it easy to see at a glance. For example, here's a board with a double open three:

board: [

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "B", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "B", "X", "B", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "B", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""],

["", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", "", ""]

],

AI can quickly provide various test cases, but human intervention is still unavoidable. After all, some edge cases and specific test cases are still difficult for AI to generate. Fortunately, here we only need to change the positions of the stones on the board, which is convenient for humans to do.

Test run results:

With test cases as a guarantee, the implementation of forbidden moves here is basically problem-free. However, if we look carefully at professional forbidden move rules, we find there are still some very professional non-forbidden move situations. We'll see how to implement these when we have more time and energy later.

Can AI Write Large Projects?

Single-player Gomoku with forbidden moves is actually quite complex, and Claude's implementation is quite good. In fact, even larger projects, like this entire site, were quickly completed with the assistance of Claude3.5 and Cursor.

Initially, I just wanted to experience Claude3.5's capabilities by writing a few simple pages. Gradually, as I wrote more, the pages of this demo site increased, and the features became richer. Recently, the Cursor editor integrated Claude3.5, making the experience of writing complex projects even better.

For features that don't require complex algorithm implementation, Claude3.5 can generally implement them well if the requirements are clearly described. Sometimes the implementation is better than expected, after all, the Claude large model actually has a lot of knowledge. Combined with Cursor's file references, AI's understanding of the entire project is getting better and better. After making changes in one place, AI will even remind you to modify other related files, which is quite good.

From my experience, there are a few areas that are lacking:

- For complex logic, Claude can only implement it if the description is clear; if the developer themselves haven't figured out how to implement it, AI probably can't implement it either;

- When AI is stacking code, it sometimes provides redundant code, such as the same function appearing in multiple files throughout the project. Developers need to constantly refactor some implementations to ensure the overall simplicity and maintainability of the code.

- When you propose some incorrect ideas, Claude will try to fit them rather than pointing out your mistakes. Sometimes the errors are very obvious. I accidentally opened the code for another page, and in Cursor, I tried to modify this file as if it were the Gomoku feature, and AI really made random changes there!

To answer the question, AI can definitely write large projects, but it needs constant prompting and error correction from humans. In this process, humans are more like supervisors, providing requirements, checking quality, refactoring, and ensuring project quality.